- Home

- Marie Jevins

Extremis Page 18

Extremis Read online

Page 18

“Tony…” Geoff was, as usual, the voice of caution. “We can’t send businesspeople out into the Congolese bush as mentors. There aren’t suitable lodgings or medical facilities. Where are we going to mentor these entrepreneurs? There aren’t even research labs.”

“Give me a little credit, Geoff.” Tony rolled his eyes. “What do you think Pepper’s been doing on her overseas mission? She’s got it all worked out for Congo, because that’s where we’re going first—and, of course, because she’s smart. We’ve salvaged an old German steamship, which is being refitted now with modern tech, labs, classrooms, cafes, and cabins. It’s going to be dismantled in Dar es Salaam, then shipped by train to Lake Tanganyika, where we’ll put it back together and sail over to DRC from there. Staff will all come in via Zambia or Tanzania.”

The board didn’t seem too enthused. Tony knew what the next question was before Geoff opened his mouth.

“How do you propose to pay for this endeavor?” Refitting German steamships with the most modern technology in the world doesn’t come cheap, Tony knew.

“I’m glad you asked that, Geoff. Owen, can you pass around the next handout? Thanks.” Owen distributed the paper showing Mrs. Rennie’s calculations.

“Tony, I see huge profits here that are meant to directly fund this ‘resource incubator,’ as you term it in the handout. But I don’t understand where the profits are coming from. The phone and appliance divisions’ proceeds are intended to fund the company, not your charity project.”

“It’s not charity, Geoff. In time, there will be profit from this, but indirectly. Think of it like this: Let’s say China or the U.S. builds a road in a country with vast mineral resources. Then, whoa, a few years later they get all kinds of great advantages when they ask if they can mine in that country. Would you call that road charity? Or would you call it foresight? Or just plain smart? Our business incubator takes that strategy a step further. We get an actual percentage of ownership of companies we help start in exchange for our support.”

“Regardless, there will be a gap during which time we have no funding for this, uh…foundation.”

“Jarvis, project Iron Man licensing,” muttered Tony. The holographic projector above the conference-room table lit up, and holograms of Iron Man T-shirts, stickers, lunch boxes, and video games suddenly filled the room. Owen gasped and smiled. The board members hesitated, then pushed forward for a closer look.

“Another side project Pepper’s been working on. Iron Man licensing. Instant money, fully funding the new foundation, with enough left over to build another Zipsat satellite.”

“I have to admit, Tony, this is impressive.”

“Of course it is, Geoff. Oh, and look at this.” Tony held up a thick paper document. “I’ve agreed to demonstrate Iron Man—the new version, Extremis—for Billionaire Boys and their Toys. Not only do I get paid for the appearance, and that money goes straight to the foundation, but also—free advertising for our Iron Man T-shirts. Nice, huh? That wasn’t my idea, by the way. That was Pepper’s. Well, sort of. At least, she said if I liked the show so much, why didn’t I just go on it already and shut up about it.”

“Well, Tony,” said Geoff. “You’ve outdone yourself here. You really do seem dedicated to saving the world, and the board is behind you on that a hundred percent. But I’m looking at this handout you gave us here, and you wrote out a statement of purpose for Stark Enterprises across the top.”

“You mean the part about how our goal is to bring on the future and be a part of it? That’s really what we’re all about, Geoff. You’re not planning to argue with me about that, are you? Because if you are—”

Geoff interrupted him. “No, no. The board agrees with that statement. And that is why I’m proposing a change to your foundation.”

Tony looked apprehensively at Geoff. Uh-oh.

“Let’s change the name. Let’s call it something snazzy. Like this line you typed here.”

“Where?”

“Here.” He pointed to his copy of the handout. “Test Pilots for the 21st Century.”

Tony felt tears welling up, so he said nothing. He just stood up and applauded Geoff. And then the rest of the board members rose, too. Not only to applaud Geoff, but to applaud Tony, Owen, Iron Man licensing, and the direction in which the company was going.

Stark Enterprises was heading into the future.

E P I L O G U E

Maya awoke to the sound of a rooster crowing incessantly.

“It’s still dark, you stupid bird,” she muttered. A seven-year-old Congolese child in a tattered Obama 2008 T-shirt lay snuggled up next to her. He fluttered his eyes open, and she regretted speaking her thoughts aloud.

“Go back to sleep, kid,” she whispered. But already, the twelve other people sleeping in the canvas-covered bed of the old Mercedes truck were stirring and stretching. None of them had slept all that well on the sacks of flour, onions, and live goats that served as a communal mattress. There was no way they could ignore the rooster-snooze-alarm.

She heard the cab doors open, then both the driver and truck mechanic rolled out and landed in the mud bog under the truck.

“Bonjour,” said the driver. He was cheerful even though he’d spent the night in a bog after driving for fourteen hours yesterday. “Let’s dig out the bus and get going,” he added in French.

A few of the passengers climbed out, and one middle-aged Zambian man in acid-washed jeans with fake gem studs on them handed out shovels and pickaxes from the back of the truck. Six men tackled the muddy bog in the first light of the morning sun. They’d alternately dig out mud, then stop long enough to find rocks, which they’d throw under the tires, rebuilding the road as they went.

The steady slap and thud of tools digging in the mud was rhythmic, and Maya dozed off for another hour. Eventually, she heard the truck start up.

“D’accord,” yelled one man. “Go ahead.” He signaled thumbs up to the driver, and everyone on the ground stood back.

The driver revved the engines, then slowly put the truck into gear. It lurched forward. He switched gears furiously, one foot pressed down hard on the accelerator, the other foot stabbing at the clutch. The truck slid back, and he gave it gas again. Back and forth, back and forth the driver rocked the Mercedes. Maya would have been alarmed, except that something like this happened every time she went to a village to assess a tech entrepreneur’s potential market.

The tires burned black smoke. The driver cut the engine.

The passengers sighed. A grandmother in eyeglasses and an orange-and-brown wax-print dress and head wrap put her feet up on a sack of onions. The men who had been digging the truck free went back to work, digging out more mud and dropping more rocks in under the tires. Maya noticed the tire had barely any tread left. How old was this truck?

The rooster was still crowing, and the goats in the back of the truck were bleating now, desperate to get free of the ropes around their ankles.

“I know the feeling,” said Maya. She wore an electronic-surveillance ankle bracelet that was impossible for her to remove on her own.

Just then she heard the sounds of greetings.

“Bonjour!” Two men, clean of mud, had approached, walking from down the road.

“We have come here to find you,” said the older man in the clean, pressed suit jacket. “We were waiting in town, and the bus—it is very late.”

“Let’s go find the bus, said my father,” added his son, a younger man in jeans and a Green Bay Packers T-shirt.

“Town is close by?” Maya interrupted them.

“Of course, madam,” said the son. “If you had all just walked two kilometers, you could have had dinner, then stayed the night in beds, under mosquito nets, in the guesthouse. We watched a football game in town last night. An enjoyable evening.”

The passengers sighed. The grandmother shook her head and smiled. She’d been facing life’s little disappointments for sixty-five years.

“May I walk back with

you?” Maya asked.

“Mais oui.”

Maya handed the kid in the Obama shirt to his mother. She took off her flip-flops, then slid down out of the truck bed, landing barefoot with a squish in some reddish mud.

“Oh, ick,” she exclaimed involuntarily. The son extended an arm to Maya, and she handed him her knapsack and flip-flops. She waded out of the bog.

The Congolese giggled at Maya’s horrified expression as she stared at her mud-caked feet. Then the father gallantly took her by the elbow and walked her to a large puddle. He pointed to the rainwater, then to her feet. Yes, that seemed like a good plan.

Maya rinsed the mud out from between her toes, then reached out to the son for her flip-flops. She eased herself out of the puddle and gently tip-toed to dry off on the grass.

“Shall we go?” The other passengers waved cheerily. They’d see Maya a few hours, or maybe a day, later. Whenever the sun and shovels cooperated to get the truck moving again.

She followed the father and son, moving from the grass to the potholed dirt road as her flip-flops dried. They walked single file, using the ridges between potholes almost as balance beams between the puddles. The mud bogs that were so dangerous to a truck were easily skirted on foot.

“C’est bon, madam?” The father occasionally turned to check on Maya. She smiled and nodded. Yes, she’d spent the night curled up with goats and children, but there was something impossibly optimistic about the rising sun on an African morning. Here were people who owned very little—maybe some goats, chickens, and a mobile phone—but they were kinder to her than anyone had been at home. She thought she understood why now. At home, she’d allowed the stress from her job to carry over into how she dealt with people. She’d been angry when driving, rude to supermarket cashiers, and furious with colleagues. No wonder she’d been miserable. And people had been miserable to her in return.

Maya took a deep breath and inhaled fresh, clean air that seemed to float over directly from thick rainforest a half a country away. Then she caught a bit of her own insecticide with her morning air, and choked for a second. The son glanced at her quickly, saw that she was fine, and continued walking.

Maya heard more than just their footsteps now. She heard chickens pecking at their morning feed and the distant sound of children playing. The father and son led her through fields to the center of town, a dirt strip surrounded by about ten large, brick buildings and a dozen smaller buildings made of mud and wood.

There was no traffic in town aside from motorbikes, chickens, and bicycles. The father and son led Maya straight to the town guesthouse, a rugged, brick building that acted also as café, bar, television venue, and mobile-phone refill center. Aside from a small church on the other end of town, this was the center of village life.

“Do you have a shower here?” Maya felt gross. She’d slept covered in DEET to avoid getting bitten by mosquitoes in the open air.

“Oui,” said the shopkeeper, a tall, bald entrepreneur dressed all in white, which was remarkable given the dust in the countryside. He fetched a bucket and towel, then motioned to her to follow. Behind the restaurant was a cinderblock building covered in a corrugated sheet-metal roof, divided into two small compartments. He stopped to fill the bucket at a spigot, then carried it into one of the compartments. He motioned her in, holding open the ramshackle door for her.

“Merci,” said Maya, taking the towel. She stripped off her dirty clothes and hung them high on a nail hammered into the side of the doorframe. She splashed herself with the water using a plastic mug she found floating in the bucket. She doused her electronic ankle bracelet, but that didn’t matter. Damn thing was waterproof. Probably nuclear-war proof, she figured.

I need to remember to carry soap on these expeditions, Maya thought. She’d had to remember a lot of things on her forays into the Congolese countryside. The contrast between her high-tech cabin back on the ship in Lake Tanganyika and the situation here was stark, though the locals didn’t seem to mind anywhere near as much as she did.

She’d carried peanut butter, bug spray, bread, plastic utensils, a sheet, treated water, a fork, duct tape, antibacterial gel, toilet paper, and a utility knife along, but these day-long expeditions never lasted only a day. The condition of the roads and “bus,” as the locals called the truck, were such that breakdowns weren’t just common, they were a given. She was torn between being more prepared or just going local. The Congo residents were stoic, sleeping in the clothes on their backs, seemingly unworried by their lack of packable duct tape.

Still, working on Stark Enterprises’ tech incubator on site in Congo was preferable to the four months she’d spent in prison back in Texas. She’d only seen the sun once a week, for twenty minutes at a stretch, had only water and milk to drink, and hadn’t been fond of the high-fat diet or the once-weekly towel exchange. She’d been able to buy candy or chips from the commissary, but the occasional cheap chocolate bar hadn’t exactly made the situation tolerable. She’d been allowed to choose books off the donated books cart, but there was barely anything worth reading. Awful books, bestsellers and romances. Books about implausible science experiments gone wrong, where the author just threw in some tech terms to dazzle the reader. Maya was an avowed atheist, but she’d even read the Bible out of desperation.

She was glad now to have studied the Bible in prison. So many of the people she met in the countryside were devoutly religious.

And then Maya heard a distant roar of engines over her splashing. The truck had made it out of the bog. But also, there was a second sound. A familiar sound. One she knew all too well.

Boot jets, she thought.

“Madam Maya,” Maya heard a small child calling to her from outside the shower.

“Un monstre! The monster wishes to see you, please come!”

Outside of the FBI, only one person could find her no matter where she went. Only her supervisor had access to the Zipsat tracking signal emitted by her ankle bracelet.

“Tell Iron Man to wait. I’m not hurrying for him.”

Tony Stark. Maya tried to work up the hatred she’d felt for him during those months in prison, but found she could not. She tried then to remember the passion she’d had for him in the early days—years ago, when she’d seen only his brilliance. Before she realized how frail Tony’s ego was, how damaged he was from growing up with an inattentive, wealthy, alcoholic genius for a father. Before she saw him use the attention of women to make himself feel more appealing and desirable.

Maya could find neither hate nor love within her soul. To her surprise, she felt only compassion for the people she was helping. Back at Futurepharm, she’d been singularly devoted to her job, had never socialized, and had few friends. Here, people accepted her easily, made her laugh, and gave names and faces to the bigger world she’d always imagined herself to be helping. When she thought of the man she’d injected with the last remaining Extremis dose, she was surprised at her own ambivalence. She’d never expected to put Tony Stark’s betrayal behind her so quickly.

She remembered her fury at Tony. Here was a man who had failed to stop Mallen outside Houston, whose failure had killed several people in fiery car crashes. A man who was never punished for his failures, while she had been sent to prison and forbidden access to all medical technology, to all the tools of her field. Tony was allowed to walk freely in spite of creating weapons that still haunted former fields of war, while she had been punished simply for running a research trial.

Stark was no longer a weapons designer. Now he was a walking weapon. Or had the potential to be. What would happen if he ever lost control? If he started drinking again? Long-term, Maya’s serum hadn’t been tested. What if it reshaped Iron Man again, in ways he didn’t anticipate?

But that was the future. Right now Tony was out flying around the world enjoying himself, while Maya was stuck in Congo, restricted to a 100-mile radius. Sometimes she fantasized that the bracelet on her leg would shut off so she could disappear into the forest. She�

��d head west by truck to Kinshasa, then across the river to start the long journey north through Gabon, Nigeria and Senegal—all the way to Morocco, then by ferry to Spain. What she wouldn’t give for some tapas right now, and a day on the beach of the Mediterranean.

She finished cleaning herself up as best she could, dried off, and put her dirty clothes back on. Maya dumped the bucket of gray water out on a small vegetable garden behind the brick shower shed and headed back up front to the cafe, her hair still sopping wet. She was quickly covered in sweat again from the heat of the day—she’d need another shower later.

Maya could see Iron Man up at the town’s dirt road, where the arriving truck had parked without bothering to move to one side or the other. There was no other traffic here.

Iron Man hovered against the sky, his boot jets firing dramatically as he sparkled red and gold against the bright-blue morning. He held the front of the truck aloft while the truck mechanic lay underneath, cleaning up after the journey over rocks and mud.

“Un moment,” yelled the mechanic from under the Mercedes.

“Pas de probleme,” said Tony. “Hey, Maya.”

She hadn’t realized Tony had seen her—but of course, he didn’t have to. Her ankle bracelet would have registered on his HUD.

The mechanic crawled away from the truck and stood up, giving Iron Man a thumbs up. Iron Man lowered the Mercedes gently, without so much as a bounce.

Iron Man’s hydraulics hissed ever so slightly as his engines cut, and he landed with a faint clank. Maya noticed with some satisfaction that he’d gotten mud on his shiny armor.

A small child cowered, fled to Maya, and hid his head in her armpit.

“C’est bon, kid. It’s okay.” Maya patted the little boy on the back.

Iron Man walked over to the café now. He didn’t clank as much as he used to, Maya noticed. The more intimate control Tony had over the suit now made it more a part of him, less a prosthesis.

Tony looked at the plastic chair where Maya was sitting and shook his head. “Suit off,” he said. The joints inside the suit disengaged, parts of the armor retracting and others simply hovering. “Fold,” said Tony. The suit folded itself up into a small, neat package, which lowered itself on to the ground.

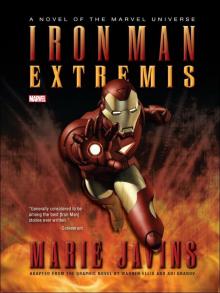

Extremis

Extremis