- Home

- Marie Jevins

Extremis Page 3

Extremis Read online

Page 3

“Knowing that it had to be done: That doesn’t ease the burden.

“All the e-mails are on the machine, if you can find them. I can do that much. But understand, this had to be done.”

Did it? Dr. Killian had asked himself this for weeks. And no, there was no other way out. Or was there? Was he justified? What if he was wrong? If you did something horrible that cost a few dozen lives, but thousands were saved, were you right in sacrificing the few? The math worked. Statistically, he was right. He was a scientist; he believed in facts. But he’d realized during the last few days that being logical did not exempt him from being human. He still felt guilt, and he couldn’t live with that guilt any more than he could survive an interrogation.

“I’m shaking. Getting hard to type. Goodbye.”

Dr. Killian sent his document to print, but made no motion to get up and walk to the printer. Best to leave it there, where it would stay clean.

He shut down his computer. Yes, he’d give them all the information they needed, but he had state-of-the-art encryption on his hard drive. That would give Extremis plenty of time to take hold, to demonstrate its awesome and innovative power and abilities, and would keep out all but the most determined hardware and software engineers. The FBI might get in after weeks of effort, but none of his colleagues would. Their brilliance was in biology and medicine, not software hacking.

This had to be done, Dr. Killian thought again. He slid open the desk drawer to his right, revealing a loaded pistol. He heard Dr. Hansen hang up the phone and swear. She threw something, and it thudded against their shared wall. The reporters were getting on her nerves. She’d be in here in just a minute, would pick up the note from the printer. Would call the paramedics from her cell phone. He’d have to do this right, so she’d be better off calling the county morgue.

He carefully released the gun’s safety mechanisms, checked the magazine, and turned the barrel around. He checked the website where he’d bought the handgun one more time to confirm he’d done all this correctly, since he’d never used a gun before. He placed the barrel squarely between his eyes, then moved it into his mouth, instead, and pointed it upward. He thought about the impersonal signs on bridges back home, back east where he’d spent his formative years, the ones imploring would-be jumpers to call a telephone number rather than jumping. He’d rather have jumped back home, he thought, where he’d have ended up a paragraph buried deep in a daily tabloid rather than the subject of the front-page drama that was likely to unfold here. Blowing his brains out seemed a bit gory. He’d lived his life in this box, and he would end it here. At least he’d give some color to the drab beige cubicle, a little joke no one else would understand. His wife would have, if he’d had a wife.

“I’ve never been in love,” he said aloud. He didn’t care whether anyone heard him. In moments, nothing he’d said would matter. “Never. No one’s ever loved me.”

He felt warm tears rolling out of his eyes, stinging his pores as they slid down his cheeks. He’d never imagined his life would end this way, never considered such a solution before. His actions with Extremis had been necessary, of course, but he hadn’t expected the guilt, or the shame. God, the shame! He was a respected scientist. He couldn’t live with it. In time, when Extremis had been used to save lives, perhaps people would understand.

Dr. Aldrich Killian pulled the trigger.

T W O

Tony stood in front of the ten-foot-tall plate-glass window behind the oak desk in his ninth-floor office, overlooking Luna Park, the Cyclone, the boardwalk, a strip of sand, and the Atlantic Ocean beyond. He could see his fans outside the Stark Enterprises gates. Something was happening down there. They were pushing and crowding each other. Either Iron Man had just shown up—which was unlikely, since Tony was Iron Man—or some generous soul had just given them all free rides on the Wonder Wheel.

Mrs. Rennie will come up with something novel as revenge, Tony realized. She hated heights. With any luck, she’d be put into one of the cars that wasn’t fixed to the rim. The sliding cars were perfectly safe. But that didn’t mean she’d appreciate their safety record when her car suddenly careened along a rail from hub to rim.

He rather enjoyed her surliness. Not that he’d ever tell her. And he’d never tell Pepper how entertaining Mrs. Rennie was. He wanted Pepper to come back, of course. Her efficiency and competence were essential to the workings of Stark Enterprises; he wasn’t sure the company could survive without her. And then there was her charm, her warmth and humor, and how stunning she looked in a low-slung, backless evening gown. Mrs. Rennie couldn’t really match her on that front.

The office door opened. Tony didn’t turn around. He could see his reflection—that was a nice new suit Mrs. Rennie had sent over, and he looked great in it—and behind him, two figures entering the room with a tripod and a camera. That would be the documentary team.

“Coney Island,” Tony mused aloud, sweeping his right arm to indicate the panoramic view below. “My dad used to tell me this was the most fantastic place in the world. The amusements. The constructions.

“See the Parachute Jump? A steel engineering marvel of the 1939 World’s Fair, New York’s own Eiffel Tower. Amelia Earhart made the first jump from its precursor, and it stayed lit all through the World War II blackouts. And the Wonder Wheel? Forged on site in 1920.

“People believed they had to be living in the future, to be able to visit an incredible place like Coney Island. And at night they wouldn’t go home. They’d sleep on the beach, so they could wake up here, in the future.

“They don’t sleep on the beach anymore. The Parachute Jump hasn’t even been in operation during my lifetime.” Tony turned around. The cameraman—or camera-intern, more like it—was already setting up the tripod. His boss, a white-haired man of about sixty, looked a little older than he had in the publicity stills Tony had seen.

“I’m sorry,” said Tony. “Mister Bellingham, yes?”

“John Bellingham. Thank you for your time.”

“Not at all. I’m an admirer of your documentaries, Mister Bellingham. Shall we get started?”

Bellingham sat down first, using his arms to slowly lower his body into the padded guest chair in front of Tony’s desk. He moved deliberately, like a man carrying a burden. Like a man who had seen many things over during the decades, and who felt those things weighing upon his entire being.

“You’re very kind,” said Bellingham. “Gary, you want to set up?”

Bellingham didn’t take his eyes off Tony as he addressed the cameraman. Tony realized that while Bellingham’s actions were mechanical and seemingly innocuous, his eyes took in everything. His mind absorbed all he was seeing. But Tony had been transparent in recent months, since he’d admitted to the world he was Iron Man. He had nothing to hide.

“I’m cool,” said Gary. “So long as you stay there and Mister Stark is behind the desk. I’m going to close the blinds, though. Nice view up here.” He walked to the window and swiveled his head left, then right. He looked quizzically back at Tony.

“Sorry,” said Tony. He spoke into his phone. “Close blinds.”

The blinds slid silently, vertically across the windows, blocking out the sun.

Tony reached across his desk to shake Bellingham’s hand.

“What’s the name of this film again, Mister Bellingham?”

“Ghosts of the Twentieth Century.”

“Hm. Okay.” Tony wasn’t sure he liked the sound of that. He thought about the abandoned Parachute Jump—and about the old Thunderbolt roller coaster, once an innovative marvel, demolished as an eyesore a decade ago. What exactly was Bellingham’s point?

“Ready, Gary?” Bellingham wasn’t interested in Tony’s hesitancy.

“Speed. In your own time, John.” Gary hit the record button and nodded to Bellingham to start whenever he was ready.

Bellingham sat up straight and held a manila envelope within view of the camera.

“I’m here at the Coney Islan

d office of Stark Enterprises with the company’s founder, CEO, and head technologist, Anthony Stark,” began Bellingham.

“Tony’s fine.”

“Tony.” Bellingham stared across the desk, his lined face suddenly becoming accusing and deliberate. “Would it be fair to define you as an arms dealer?”

Tony had anticipated this line of questioning and was ready for it. “Absolutely not. I am a social entrepreneur, and Stark Enterprises has ceased all weapons research. I admit that up until recently—”

Bellingham interrupted. “But Stark did design and sell arms for decades?”

Tony kept his expression unchanged. “I wouldn’t deny that we have designed arms for the U.S. military, of course. This is well-documented.”

“In fact,” continued Bellingham. “It’s your heritage, how you made your millions, why you can afford to step back from weapons today and still have a company. Stark Enterprises was founded on weaponeering, I believe.”

“My first major contract was for the U.S. Air Force, yes.”

“What was that contract?”

Tony’s face stayed calm. Bellingham’s line of attack, so far, was accurate and not unexpected. “My initial engineering interest was miniaturization. The USAF saw applications in munitions.”

“And that was the seedpod bomb, yes?” Bellingham had done his research.

“It was the same process, however, that led to—”

“The seedpod was first used in Gulf War One? How old were you?”

Tony hadn’t thought about this in years. He’d been a kid, working with DIY gear in his room at night. “I was a teenager.”

“Now correct me if I’m wrong. But the seedpod dispensed hundreds of ‘smart’ micromunitions from a mother-bomb casing, yes?”

“As I said before, Stark no longer makes weapons, including the seedpod,” said Tony. “But, yes, it was intended to destroy airfields and cripple armored convoys.”

“Did it work?” Bellingham surprised Tony now. “Did all of those bomblets go off as anticipated?”

Tony thought quickly. Bellingham was presenting classified information on camera. “You’ll have to ask the military. We never got an operations report on every single micromunition. There were tens of thousands—”

“Perhaps you’d like to look at these pictures.” Bellingham handed over the manila envelope.

Aware that his reaction could imply much about the envelope’s contents, Tony accepted and opened the folder carefully. He pulled out a group of photos and paged through them, carefully shielding the distressing images of dying and injured people from the camera lens.

“Each one of your bomblets has the explosive force of three sticks of dynamite,” continued Bellingham. “Eighteen percent of them suffered time failures. They’re scattered across the theater of conflict.

“Children find them, Tony.”

Tony could see the cameraman zooming in on his face. He did not visibly react.

“Can you tell us what the Stark Sentinel is?” Bellingham wasn’t letting up.

“It’s a land mine.” Of course Tony knew what it was. He’d designed it in his early twenties. The land mines formed the defensive line between North and South Korea. What’s Bellingham’s point here?

“You’re unaware of Stark land mines in, say, East Timor?”

“Yes.” Tony was not aware of any Stark weapons in East Timor, but he knew from his own experience that weapons had a way of showing up in unintended places. That was one of the reasons he’d quit designing them.

And he was intimately acquainted with the Stark Sentinel. That was the land mine that had nearly killed him in Afghanistan.

“Tell me about when you were injured in Kunar Province, Mister Stark. Was it an IED?”

Bellingham knew an improvised explosive device had not injured Tony in Afghanistan. He’s baiting me, thought Tony. The tan, dry dunes and scrubby brush of the Afghan desert were vividly imprinted in his memory, as was the sight of soldiers unloading Stark Sentinel mines from armored military vehicles.

“Our convoy had stopped outside a base,” he said, neglecting to answer the question. “I was consulting.”

“By consulting, do you mean showing off your latest deadly inventions? Trying to sell them?”

Tony ignored the slight.

“When I looked the base up online, soldiers had posted reviews of it. ‘Great place to take the family. All that’s missing is a carousel.’ And you should see the fake cooking-show videos they’d posted of Meals Ready to Eat. You wouldn’t believe what those guys do with jalapeno cheese spread. Our soldiers are young people making a living, patriots with families and hopes and dreams. They deserve to be protected, Mister Bellingham. And yes, I was making a great deal of money keeping them safe. But don’t you see? I did keep them safe. Hundreds of lives were shielded from harm by Stark technology, and millions more from medical advances that evolved from that same technology.”

Tony had not been in Afghanistan—looking at ways to contain insurgency, save lives, and keep the world at peace—out of the goodness of his heart. He’d gone there to make money selling a new batch of weapons to the military. He wasn’t proud of this. He was brilliant, one of the smartest visionaries on the planet. So why hadn’t he realized his powerful, impossible-to-duplicate weapons were uniquely lethal, and that they would tempt all but the least corruptible with their high values on the black market?

Lost in thought, he remembered the airmen he’d watched as their futures evaporated in a rush of gunfire and blood. The general next to Tony had fallen, too, his hat and cigar crumpling as he collapsed lifeless to the road, speckled with shrapnel from a rocket-propelled grenade. Land mines spilled from the truck, but Stark Sentinels were not supposed to go off on their own. They had to be set.

And then more bullets came. From where? Tony didn’t have time to consider that, back during field tests, he’d failed to study the effect of bullets hitting unarmed mines. As he watched the mines targeting, exploding, all he’d had time to think about was impact, fire, dust, pain, and the warmth of his own blood spreading across his chest.

“I’m fine now, thanks.” Back in the present, Tony answered the same question he always heard about his injury in Afghanistan. But Bellingham hadn’t asked it.

“Was that before or after you sold the supergun to a Gulf state?”

“I’m afraid that’s classified information.”

“But you did design a gun with a half-mile-long barrel intended to lob tactical nuclear devices some four hundred miles?”

Tony had security clearance, but everyone who would watch this documentary did not.

“I would like to be able to comment. But I’m under restrictions on that subject.”

“I see,” said Bellingham. “How many of these devices led you to the design of the ‘Iron Man’ suit?”

Ah, now Tony saw where Bellingham was going. This whole interview was about Iron Man. About demonizing his most brilliant invention.

“All tools have destructive potential.” Tony picked up a pen and notebook to idly sketch the Iron Man armor. He jotted down a new idea: a way to use window glass to capture sounds via a laser array in the chest plate. Then he looked back up. “The repulsor has applications for cheap, non-chemical space launch.” He’d been thinking about that for a while, but Stark’s new lack of military funding had limited his ability to research.

“I see. And are you developing that?”

“Not at this time.” Tony stopped sketching and scratched his chin. He was committed to Stark Enterprises’ new mission. But for all his genius, he couldn’t work out how to make peace-for-profit more financially rewarding than war profiteering.

“The Iron Man armor is just another defense-industry application, isn’t it? You use it for special-response peacekeeping, like with the Avengers. But that’s just privatized defense. You’ve just made a new defense application, right?”

“My point—and I don’t want to talk over you, John, but you�

�re not giving me credit for anything good that’s come out of our past military funding—my point, John, is that Stark microelectronic breakthroughs have all led to useful social technologies after they were initially funded by military research.”

Tony pointed angrily across the table. “No, I didn’t first think to myself that taking microchips down to the nanometer limit would be good for bombs. But that’s how we made the money to expand our research, and the money from seedpod was driven into biometric medicine and internal analgesic pumps. I’m not involved in weapons design now. But yes, I was. And I question every day whether that was the right call, to make bombs in exchange for medical advances.”

Bellingham sat back and crossed his arms.

“Do you think they have your painkilling drug pumps in Iraq? Do you think an Afghan kid with his arms blown off by a land mine is remotely impressed by an Iron Man suit?”

Tony sat quietly for a moment. He’d been wrestling with this for weeks now, wondering whether one injured child was too many.

“I never claimed to be perfect,” said Tony quietly. “Yes, there is blood on my hands. But I’m trying to atone…Iron Man is the future. I’m trying to improve the world.”

“Improve the world. Right. Thanks for your time.” Bellingham stood up. Gary hit the pause button on the camera, then stop. He collapsed the tripod.

Bellingham spoke again to Tony. “I’m curious, actually. If you know my work—clearly, I was going to give you a hard time—why did you agree to this interview?”

“Me first,” said Tony. “Why am I a ghost of the twentieth century?”

“Because your earlier arms work still haunts the poverty- and war-stricken countries it was deployed in.”

“I wanted to meet you,” Tony explained. “You’ve been making your investigative films for what, twenty years now? I wanted to ask: Have you changed anything? You’ve been uncovering disturbing things all over the world for two decades. Have you changed anything?”

Bellingham stood in silence. He was used to asking the hard questions, not answering them.

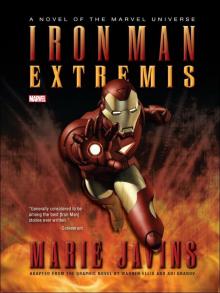

Extremis

Extremis